✒️ By Pouya Nekouei - 27 July 2021

The sonic history of Modern Iran is an understudied field, in need of increasing focus and attention by scholars of modern in Iran in a variety of disciplines, particularly history and ethnomusicology. If we look at the large volumes of sound data that has been available to us since the emergence of audio technology in the early 20th century, the extent of writings on modern Iran, including the history of modern Iran that draws on sound-based documents has the potential to increase drastically.

Unfortunately however, until now, sound records have not been regarded as serious documents by many scholars with interests in modern Iran. Sound documents and sound histories, experiences and modes of listening in the Iranian context - as cultural historians of music have discussed - have gone into oblivion and forgetfulness by two predominant groups interested in sound within Iranian academia: (1) historians and (2) ethnomusicologists.

Traditionally, historians in Iran – even to a large extent today – have been interested in traditional historical sources and documents, by rendering only these to scrutiny and test of veracity. Although in recent years, historians of modern Iran have increasingly tended to take the benefit of multiple oral and visual sources to study modern Iranian history, sounds and sound documents are yet to find their place in Iranian history departments.

Ethnomusicologists, although dealing with sound materials and specifically music, have a complicated relationship with such documents. Ethnomusicologist in Iran - of course naturally - have treated sound as music. Iranian ethnomusicology, I submit, has an uneasy relationship in treating the musical data available to us over the past hundred years in an unbiased manner. I have illustrated on various occasions that the question of music as sound and more importantly as a historical document, which could potentially be used within a larger historical narrative is the “Achilles’ heel” of Iranian ethnomusicology and its current dominant discourse.

Although critical research in the field of ethnomusicology in Iran has grown over the past decade, the shadow and problems that ‘high art’ or ‘art music’ has cast over the discourse of the discipline remain. Hence, in borrowing from Mohammad Tavakoli-Targhi who speaks of textual sources in different contexts, sounds are “homeless documents” within the Iranian higher academia; these sources are neither taken seriously by historians nor by ethnomusicologist in Iran whose profession is still dominated by treating music largely as ‘high art music’.

In what follows, I have succinctly pointed to the multiple nature of audio documents in Iran. There are different audio documents on various record formats that could be used in various research questions on modern Iran. From the late Qajar era until the late 1950s, 78rpm records played multiple roles in social, cultural and political life of sound and music in modern Iran. These records took on various functions in the Iranian society and, for instance, made listening a shared experience in the Iranian public sphere. Although much research is required on the role of records and audio technologies in Iranian history, it is clear that 78rpm records not only made music available, but also took on other roles : recording family voices for instance was one such function.

As Amir Mansoor has showed, at least from the 1940s, these records were used by family members of Iranians overseas, as far as Europe, in order to communicate with their family members. The author has also heard 78rpm records used by Iranian politicians in the 1940s; among these for instance Dr. Aliakbar Siyasi’s record is a notable example. Therefore, the function of these records, although predominantly musical in nature, was certainly was not limited to it.

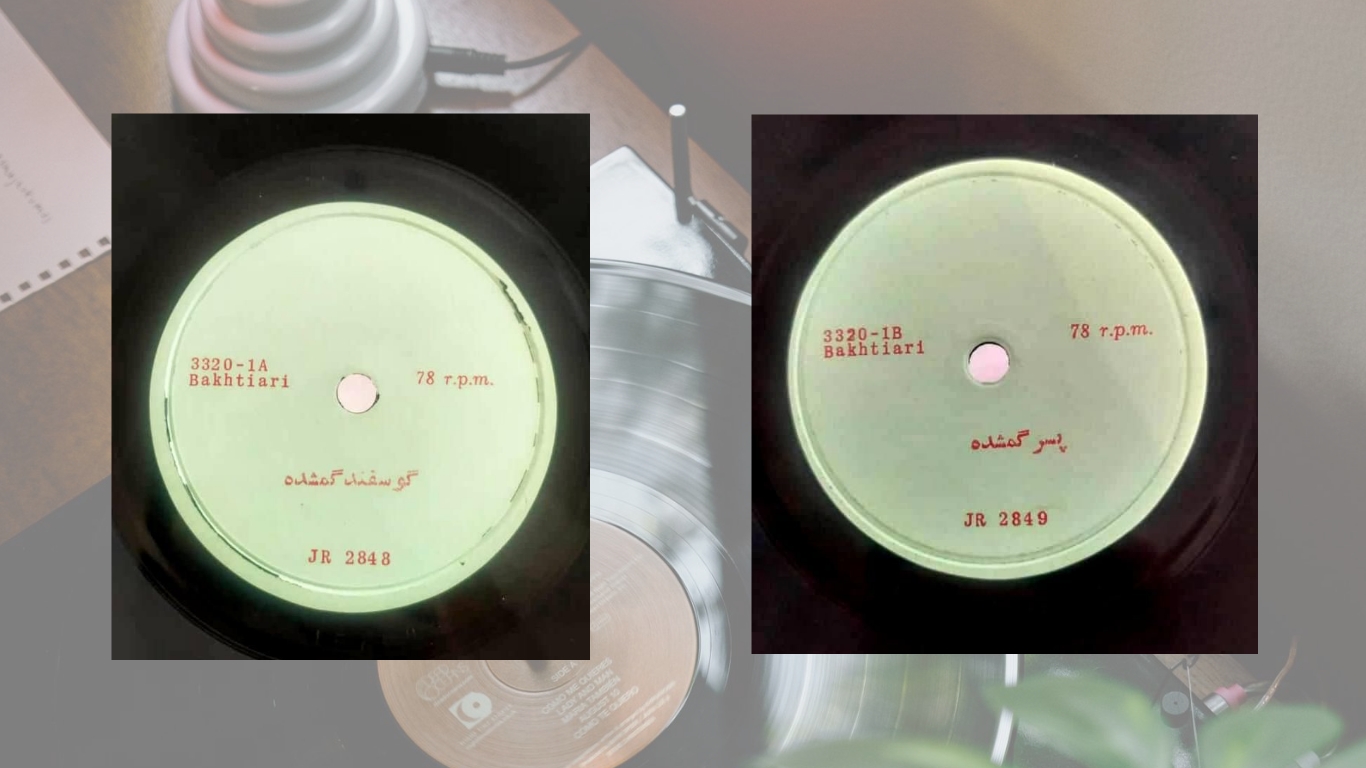

Another important role the 78rpms played was to spread religious and missionary activities in Iran during the Pahlavi era. Below, one such document is introduced. I have also made available the sound and labels of the document from my personal collection. The label is blue but has no trademark. Although the format is 78rpm. The material however, is not made of shellac and it is similar to the vinyl. The first side is titled “The Lost Sheep” and the second side is titled “The Lost Boy”. On both sides there is a narrative taken apparently from the bible, but interestingly performed in Bakhtiari dialect which was prevalent in parts of South-West Iran. On the label, the title “Bakhtiari” is mentioned in referring to this famous region, inhabited by the Bakhtiari clan.

AUDIO-Lost Boy - Lost Sheep.mp3

The record also has matrix numbers as well as catalogue numbers on both side, a clear indication that these records were not made privately, but were rather officially produced. In the conclusion section, the narrator ends his narrative by inviting the audience to the “right path” in life, that is Christianity and the bible. The Bakhtiari dialect of this record is an interesting indication to missionary activities during this time in the southern part of Iran. Others have testified to the existence of similar records in other Iranian dialects, driven by missionary goals. Some of these dialects appear to be extinct today. From other similar available records and the material of the record itself, this conjecture is proposed that the record’s production and release – although not certain – was perhaps concurrent with the rise of the government of the Iranian national front under the premiership of the late Dr. Mohammad Mossadeq, early in the 1950s.

There are historical hints that during this period various records were produced, in order to invite people from different regions in Iran to Christianity. This record and similar ones are important non-musical records in the sonic history of modern Iran that used Iranian dialects in order to influence people. We are uncertain of the extent and reach of such records, but there is no doubt that these sound documents were produced to influence various groups and regions in Iran. While there might not be much musically significant data in such records for ethnomusicological studies, these documents, if used within the larger relevant context, could certainly be valuable to interdisciplinary studies on modern Iran, including for historians.

Consequently, one disciplinary and methodological exigency for historians of modern Iran, as Dariush Rahmanian (Mardomnameh’s Editor-in-Chief) has pointed out on various occasions, is to pay attention to various sonic documents alongside other sources such as visual, oral and textual materials.

Pouya Nekouei is a PhD Student of Ethnomusicology at The Graduate Center, City University of New York